Chapter 7 Examining the involvement of the speech motor system during rumination: a dual-task investigation

t has been suggested that verbal rumination may be considered as a form of inner speech and may therefore recruit the speech motor system. This study explores whether the speech motor system is involved in verbal rumination by examining the effects of articulatory suppression (via gum-chewing) on two forms of induced repetitive thoughts (rumination and problem-solving), following the presentation of a stressor. We expected that (unconstrained) rumination would lead to sustained negative affects following a stressor whereas (unconstrained) problem-solving would lead to less detrimental effects on mood (in comparison to rumination). However, if motor processes are involved during rumination and problem-solving, articulatory suppression should dampen the differential effects of rumination and problem-solving on mood. At the time of the writing, data collection is still ongoing and the analyses presented in this chapter are therefore very preliminary. However, data collected so far suggest that articulatory suppression (gum-chewing) is indeed associated with a weaker difference in the effects of rumination versus problem-solving on state negative affects.52

7.1 Introduction

The ability to talk to oneself silently is a central ability that supports many higher cognitive functions such as remembering, planning, task-switching or problem-solving (for review, see Alderson-Day & Fernyhough, 2015; Perrone-Bertolotti et al., 2014). Although inner speech supports many cognitive abilities, its dysfunctions are similarly numerous and diverse. For instance, auditory verbal hallucinations (which can be conceived of as intrusive and agency-defective inner voices) or obsessional thoughts can be considered as occurrences of dysfunctional inner speech (Perrone-Bertolotti et al., 2014). In the present article, we focus on rumination, a form of repetitive negative thinking (Ehring & Watkins, 2008) than can be broadly defined as unconstructive repetitive thinking about past events and current mood states (Martin & Tesser, 1996).

Rumination has been consistently related to increased risks of onset and maintenance of depressive episodes (for review, see Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008) and has been suggested to contribute in exacerbating current depression (e.g., De Raedt & Koster, 2010). A particularly maladaptive and harmful form of rumination is brooding, defined as self-critical pondering on one’s current or past mood states and unachieved goals (Treynor et al., 2003). Brooding has been shown to uniquely contribute to the maladaptive consequences of self-focused repetitive thinking. Experimental studies have shown that induced rumination, in comparison to distraction or problem-solving, worsens (i.e., lengthens and/or intensifies) negative mood (e.g., Huffziger & Kuehner, 2009; Philippot & Brutoux, 2008), impairs cognitive processes (e.g., Philippot & Brutoux, 2008; Whitmer & Gotlib, 2012) and increases the retrieval of overgeneral and negative autobiographic memories (e.g., Lyubomirsky et al., 1998; Watkins & Teasdale, 2001).

Overall, rumination is known to be a predominantly verbal process (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Goldwin & Behar, 2012; Goldwin et al., 2013; McLaughlin et al., 2007) and has been proposed to be considered as such as a dysfunctional form of inner speech (e.g., Perrone-Bertolotti et al., 2014). Research on the psychophysiology of inner speech revealed that the neural processes involved in overt and covert speech tend to be very similar. Indeed, both forms of speech involve a landscape of inferior frontal areas, motor and auditory areas (for an overview, see Perrone-Bertolotti et al., 2014; Lœvenbruck et al., 2018). This is coherent with the idea that some forms of inner speech could be considered as a kind of simulation of overt speech (e.g., Postma & Noordanus, 1996; Jeannerod, 2006), in the same way as imagined actions can be considered as the result of a simulation of the corresponding overt action (e.g., walking and imagined walking, Decety, Jeannerod, & Prablanc, 1989). In other words, the motor simulation hypothesis suggests that the speech motor system should be involved during inner speech production.

Accordingly, in the same way that motor imagery is usually accompanied by peripheral muscular activation (for a review, see Guillot et al., 2010), inner speech production should also be associated with activation in the speech muscles. This hypothesis has been corroborated by many studies showing peripheral muscular activation during inner speech production (e.g., Livesay et al., 1996; Locke, 1970; Locke & Fehr, 1970; McGuigan & Dollins, 1989; McGuigan & Winstead, 1974; Sokolov, 1972), during auditory verbal hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia (Rapin et al., 2013) and during induced rumination (Nalborczyk et al., 2017). Some authors also recently demonstrated that it was possible to decode inner speech content based on surface electromyography signals (Kapur et al., 2018), although other teams failed to obtain such results (e.g., Meltzner et al., 2008).

The corollary hypothesis might be drawn, according to which the production of inner speech (and rumination) should be affected by a disruption of the speech motor system. This idea is supported by a large number of working memory studies using articulatory suppression to interfere with the subvocal rehearsal component of working memory, leading to impaired recall performance (e.g., Baddeley et al., 1984; Larsen & Baddeley, 2003). Although articulatory suppression usually refers to the overt and vocalised repetition of speech sounds (e.g., repeating a syllable or a word out loud), several studies have shown that concurrent subvocalisation or mechanical perturbation of the speech motor system (e.g., unvoiced or mouthed speech) could also interfere with speech planning (e.g., Reisberg et al., 1989; Smith et al., 1995). Interestingly, the effects of this motor interference are usually described as increasingly efficient depending on the degree of “enactment”, ranging from silent mouthing to vocalised utterance (Reisberg et al., 1989).

The effects of articulatory suppression on inner speech production are also known to depend on other factors such as the complexity and the novelty of the inner speech content (Sokolov, 1972). Similarly, the effects of articulatory suppression seem to vary according to the degree to which inner speech production has been automatised (e.g., rehearsing novel vs. known content, Sokolov, 1972). Therefore, inner speech might be more or less affected by mechanical constraints, depending on the type of inner speech to be produced. As suggested in the ConDialInt model presented in Grandchamp et al. (2019), inner speech might vary in form along several dimensions, such as “enactment” (i.e., the degree of implication of the speech motor system), itself related to condensation (some forms are syntactically and lexically condensed, others include full syntactical, lexical, phonological and articulatory specification). These different dimensions and varieties of inner speech have been thoroughly studied by experience sampling methods and questionnaires (e.g., Hurlburt, 2011; Hurlburt et al., 2013; McCarthy-Jones & Fernyhough, 2011) but also more recently using neuroimagery (Grandchamp et al., 2019). In light of these considerations, a central question of the present article is to elucidate whether rumination is a form of inner speech that is affected by articulatory suppression.

It has been highlighted that earworms (i.e., “involuntary musical imagery”) might share some similarities with repetitive negative thoughts such as obsessional thoughts (see a review in Beaman & Williams, 2010). In a recent study, Beaman and colleagues have shown that chewing a gum induced a reduction in the number of self-reported earworms episodes, in comparison to a resting condition (Beaman, Powell, & Rapley, 2015). However, these results should be interpreted cautiously, as the gum-chewing condition was compared to a resting (passive) condition and not to an active control condition (e.g., finger-tapping) in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2. The results of the third experiment reported in Beaman et al. (2015), in which gum-chewing was compared to finger-tapping, suggest that gum-chewing might indeed be more efficient than finger-tapping in reducing the number of self-reported earworms episodes. However, it should be noted that these results contradict several previous results (e.g., Kozlov, Hughes, & Jones, 2012) and should therefore be interpreted as suggestive.

To the best of our knowledge, only one study investigated the effects of a perturbation of the speech motor system on verbal repetitive negative thinking (Rapee, 1993). This study revealed a “marginally significant” decrease in worry-related thoughts following an articulatory suppression. In the same vein, we recently carried out a study in which we compared the effects of an articulatory suppression (silent mouthing) to the effects of finger-tapping following a rumination induction (Nalborczyk et al., 2018). The results of this study revealed, as in Rapee (1993), a marginally superior effect of articulatory suppression (compared to finger-tapping) in reducing self-reported state rumination. However, it was not clear whether this effect was due to articulatory suppression per se or to extraneous factors such as baseline differences (see discussion in Nalborczyk et al., 2018).

In the present study, we aimed to investigate whether rumination involves articulatory features by interfering with the activity of the speech motor system during rumination. To this end, we compared the effects of an articulatory suppression (gum-chewing) to a control motor activity (finger-tapping), following either an induction of (verbal) rumination or an induction of (verbal) problem-solving. We expected to find less self-reported state rumination following a period of articulatory suppression than following a period of finger-tapping. Moreover, because both rumination and problem-solving are expected to be (at least partially) blocked by articulatory suppression, we expected articulatory suppression to reduce the detrimental effects of rumination on mood (in comparison to finger-tapping), whereas we expected articulatory suppression to reduce the beneficial (or less detrimental, in comparison to rumination) effects of problem-solving on mood (in comparison to finger-tapping).

7.2 Methods

In the Methods and Data analysis sections, we report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all measures in the study (Simmons et al., 2012). A pre-registered version of our protocol can be found online: https://osf.io/8ab2d/.

7.2.1 Participants

We used the Sequential Bayes Factor procedure as introduced in Schönbrodt et al. (2017) to determine our sample size. We defined a statistical threshold as \(BF_{10} = 10\) and \(BF_{10} = \dfrac{1}{10}\) (i.e., \(BF_{01} = 10\)) on the effect of interest. More precisely, we were interested in the difference in self-reported state rumination after the period of motor activity between the two rumination groups. In order to prevent potential experimenter and demand biases during sequential testing, the experimenter was blind to Bayes factors computed on previous participants (Beffara et al., 2019). All statistical analyses have been automated and a single instruction was returned to the experimenter (i.e., “keep recruiting participants” or “stop the recruitment”). We fixed the minimum sample size to 100 participants (i.e., around 25 participants per group) to avoid early terminations of the sequential procedure and the maximum sample size to four weeks of experiment, including in total 255 potential time slots.

At the time of the writing, we were not able to conduct this procedure until its end. We currently have data for 42 participants. These participants were all female Dutch-speaking right-handed undergraduate students in Psychology at Ghent University (Mean age = 21.26, SD = 2.28). They were recruited via an online platform and were given 10 in exchange for their participation. Each participant provided consent to participate and the present study was approved by the local ethical committee of the Psychology department at Ghent University.

7.2.2 Material

7.2.2.1 Trait questionaire measures

Trait rumination was assessed using the Dutch version of the 10-item revised Ruminative Response Scale (Raes, Hermans, & Eelen, 2003; Treynor et al., 2003). This questionnaire comprises two subscales, evaluating either the Reflection or the Brooding component of rumination, where the latter refers to a less adaptive form of rumination (Treynor et al., 2003). To assess the presence and severity of depressive symptoms, we administered the Dutch version of the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II-NL, Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996; Van der Does, 2002).

7.2.2.2 State questionaire measures

State rumination was assessed during the experiment via the Dutch version of the Brief State Rumination Inventory (BSRI, Marchetti et al., 2018). This questionnaire comprises eight items measuring the extent to which participants are ruminating at the moment. These items were presented as visual analogue scales (VASs) subsequently recoded between 0 and 100. The BSRI total score is computed as the sum of these eight items and the BSRI has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Marchetti et al., 2018). Positive and negative affects were monitored throughout the experiment using the Dutch version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS, Engelen, Peuter, Victoir, Diest, & Van den Bergh, 2006; Watson et al., 1988).

7.2.2.3 Thinking-style induction

The thinking-style induction was adapted from Grol et al. (2015) and consisted in two parts. First, participants were asked to vividly imagine a car accident scenario from a first-person perspective (as if they were driving the car). They were given between 1min (minimum allocated time) and 5min (maximum allocated time) to imagine this situation. Second, participants were asked to think about this hypothetical situation and its consequences in either a ruminative manner or a problem-solving manner. To this end, a series a six prompts were presented successively on the screen (specific prompts can be found in the supplementary materials). Each prompt was presented for a maximum duration of 2min and the participant was invited to type her thoughts in reaction to this prompt below the prompt. Participants were asked to type their thoughts as they came, without focusing too much on the grammatical correctness of the sentences they were typing.

7.2.2.4 Articulatory suppression

In the articulatory suppression condition, participants were asked to open an opaque box (disposed aside from the computer screen) in which they found chewing gums.53 They were then asked to chew the gum in a “sustained but natural way” (in order to avoid too much interruption) during the next 5 minutes. In the finger-tapping condition, participants were asked to tap with the index of their non-dominant (i.e., usually left) arm at a “sustained but natural” pace for the next 5 minutes. In both conditions, participants were also asked to “continue to think about the car-accident situation and the following prompts”.

7.2.3 Procedure

Upon arriving at the laboratory, participants were asked whether they had recently been involved in a traffic accident. No participant was excluded on this basis. Participants then completed the BDI-II-NL questionnaire. No participant was excluded on the basis of a BDI-II-NL score greater than 29. Afterwards, participants were given a brief verbal overview of the experiment by the experimenter, before the experimenter definitely left the room. The participant then started the experiment on a computer. The experiment was programmed with the OpenSesame software program (Mathôt et al., 2012).

After filling-in the consent form, participants watched a series of short (around 30s each) neutral video clips for a total duration of 5mn in order to neutralise pre-existing mood differences between participants (Marchetti et al., 2018; Samson, Kreibig, Soderstrom, Wade, & Gross, 2015). Then, participants filled-in baseline measurements of state rumination (BSRI) and state affects (PANAS). Afterwards, participants went through either a rumination or a problem-solving thinking induction, as described previously. Following this induction, participants filled-in again the BSRI questionnaire to check whether the rumination induction was successful in inducing rumination. Participants in each group were then randomly allocated to either a 5-min articulatory suppression condition (gum-chewing) or a 5-min finger-tapping condition, resulting in four groups of participants. Following the motor activity, participants filled-in again both the BSRI and the PANAS questionnaires. Then, participants filled-in the RRS questionnaire to assess their propensity to ruminate in daily life.

At the end of the experiment, all participants went through a positive mood induction (remembering and reliving a positive memory) to attenuate the effects of the stress induction. Finally, participants were fully debriefed about the goals of the study. The entire experiment was video-monitored using a Sony HANDYCAM video camera to check whether the participants effectively completed the task. In addition, the experimenter was able to monitor the participant’s performance during the experiment through a one-way mirror (located behind the participant). This procedure is summarised in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1: Timeline of the experiment, from top to bottom.

7.2.4 Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3.5.0 (R Core Team, 2018), and are reported with the papaja (Aust & Barth, 2018) and knitr (Xie, 2018) packages.

To model state rumination and affect in response to the thinking-style induction and the articulatory suppression manipulation, we fitted a series of Bayesian regression models.54 These analyses were conducted using the brms package (Bürkner, 2018b), an implementation of Bayesian multilevel models that employs the probabilistic programming language Stan (Carpenter et al., 2017). Four chains were run for each model, including each 10,000 iterations and a warmup of 2,000 iterations. Posterior convergence was assessed examining autocorrelation and trace plots, as well as the Gelman-Rubin statistic. Constant effects estimates were summarised via their posterior mean and 95% credible interval (CrI), where a credible interval interval can be considered as the Bayesian analogue of a classical confidence interval, except that it can be interpreted in a probabilistic way (contrary to confidence intervals, Nalborczyk et al., 2019b). When applicable, we also report Bayes factors (BFs) computed using the Savage-Dickey method.55 These BFs can be interpreted as updating factors, from prior knowledge (what we knew before seeing the data) to posterior knowledge (what we know after seeing the data).

7.3 Results

The results section is divided into two sections investigating the effects of i) the thinking-style induction and ii) the interaction between the effect of the thinking-style induction (rumination vs. problem-solving) and the effect of the motor activity (chewing vs. finger-tapping) on self-reported state rumination and negative affects. Importantly, as data collection is still ongoing (it will continue next semester), these analyses should be considered as very preliminary. The number of observations (participants) per condition is reported in Table 7.1.

| Thinking mode | Motor activity | Sample size |

|---|---|---|

| problem-solving | chewing | 14 |

| problem-solving | tapping | 8 |

| rumination | chewing | 11 |

| rumination | tapping | 9 |

7.3.1 Thinking-style induction

To examine the efficiency of the induction procedure (i.e., the effects of time, coded as Session, and the effects of the thinking-style, coded as Think) while controlling for the other variables (i.e., RRSbrooding and BDI.II), we then compared the parsimony of several models containing different combinations of constant effects and a varying intercept for Participant. Model comparison showed that the best model (i.e., the model with the lowest WAIC) was the model including Session and BDI.II as predictors (see Table 7.2). Fit of the best model was moderate (\(R^2\) = 0.574, 95% CrI [0.372, 0.714]).

| \(WAIC\) | \(pWAIC\) | \(\Delta_{WAIC}\) | \(Weight\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(Int+Session+BDI\) | 1048.10 | 21.03 | 0.00 | 0.384 |

| \(Int+Session+BDI+Session:BDI\) | 1049.62 | 20.53 | 1.52 | 0.180 |

| \(Int+Session+RRSbro+BDI+Session:RRSbro+Session:BDI\) | 1049.98 | 21.44 | 1.88 | 0.150 |

| \(Int+Session+Think+Session:Think+BDI\) | 1050.02 | 21.70 | 1.92 | 0.147 |

| \(Int+Session+RRSbro\) | 1051.45 | 25.08 | 3.36 | 0.072 |

| \(Int+Session+RRSbro+Session:RRSbro\) | 1053.50 | 25.55 | 5.41 | 0.026 |

| \(Int+Session+Think+Session:Think+RRSbro\) | 1053.73 | 27.41 | 5.64 | 0.023 |

| \(Int+Session\) | 1054.57 | 26.13 | 6.47 | 0.015 |

| \(Int+Session+Think+Session:Think\) | 1057.31 | 28.08 | 9.22 | 0.004 |

Constant effect estimates from the best model are reported in Table 7.3. Based on these values, it seems that Session (i.e., the effect of the rumination induction) increased self-reported state rumination (i.e., the BSRI sum score) by approximately 73.89 points on average (\(\beta\) = 73.89, 95% CrI [26.034, 116.68], \(BF10\) = 36.198). The main positive effect of BDI.II indicates that higher BDI-II scores were associated with higher self-reported state rumination scores on average.

| Term | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Rhat | BF10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 235.000 | 16.252 | 204.313 | 268.589 | 1.000 | 7.405*10{}15 |

| Session | 73.890 | 22.281 | 26.034 | 116.680 | 1.000 | 36.2 |

| BDI.II | 95.109 | 15.357 | 63.435 | 124.275 | 1.000 | 6.534*10{}12 |

Model comparison revealed that the models including an interaction term between the effect of time (Session) and the effect of the thinking-style (i.e., rumination vs. problem-solving) were not ranked among the best models according to their WAIC (cf. Table 7.2). However, for completeness, we report the estimations from the model including an effect of time, an effect of thinking-style, and an interaction between these two predictors (see Table 7.4).

| Term | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Rhat | BF10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 234.989 | 22.790 | 189.201 | 276.629 | 1.000 | 1.463*10{}19 |

| Session | 74.155 | 22.365 | 29.407 | 117.956 | 1.000 | 53.32 |

| Thinking mode | -9.896 | 39.146 | -91.428 | 66.196 | 1.000 | 0.404 |

| Session x Thinking mode | 3.786 | 40.971 | -83.044 | 85.676 | 1.000 | 0.409 |

This analysis revealed that both the thinking-style (i.e., rumination vs. problem-solving) and the interaction between time and thinking-style have a negligible effect on self-reported state rumination (\(\beta\) = 3.786, 95% CrI [-83.044, 85.676], \(BF10\) = 0.409). In other words, contrary to our expectations, the rumination induction was not associated with more self-reported state rumination than the problem-solving induction (although more rumination was reported after induction than before on average).

7.3.2 Articulatory suppression effects

7.3.2.1 Self-reported state rumination

We then examined the effect of the two motor tasks (gum-chewing vs. finger-tapping) on both self-reported state rumination (BSRI) and self-reported negative affects (the negative dimension of the PANAS), while controlling for the amount of verbal thoughts reported by the participant. Based on our hypotheses, we expected that the model comparison would reveal a three-way interaction between Session, Thinking-style and the type of motor activity. However, the best model identified by the WAIC model comparison did not include this interaction as a constant effect (see Table 7.5). Fit of the best model was moderate (\(R^2\) = 0.729, 95% CrI [0.598, 0.811]).

| \(WAIC\) | \(pWAIC\) | \(\Delta_{WAIC}\) | \(Weight\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(Int+Session\) | 1019.39 | 29.98 | 0.00 | 0.393 |

| \(Int+Session+Think+Session:Think\) | 1020.39 | 30.23 | 1.00 | 0.238 |

| \(Int+Session+Motor+Verbal+Session:Motor+Session:Verbal+Session:Motor:Verbal\) | 1020.39 | 30.54 | 1.00 | 0.238 |

| \(Int+Session+Motor+Session:Motor\) | 1022.21 | 30.88 | 2.82 | 0.096 |

| \(Int+Session+Motor+Think+Session:Motor+Session:Think+Session:Motor:Think\) | 1025.10 | 31.17 | 5.71 | 0.023 |

| \(Full\ model\) | 1026.23 | 31.99 | 6.84 | 0.013 |

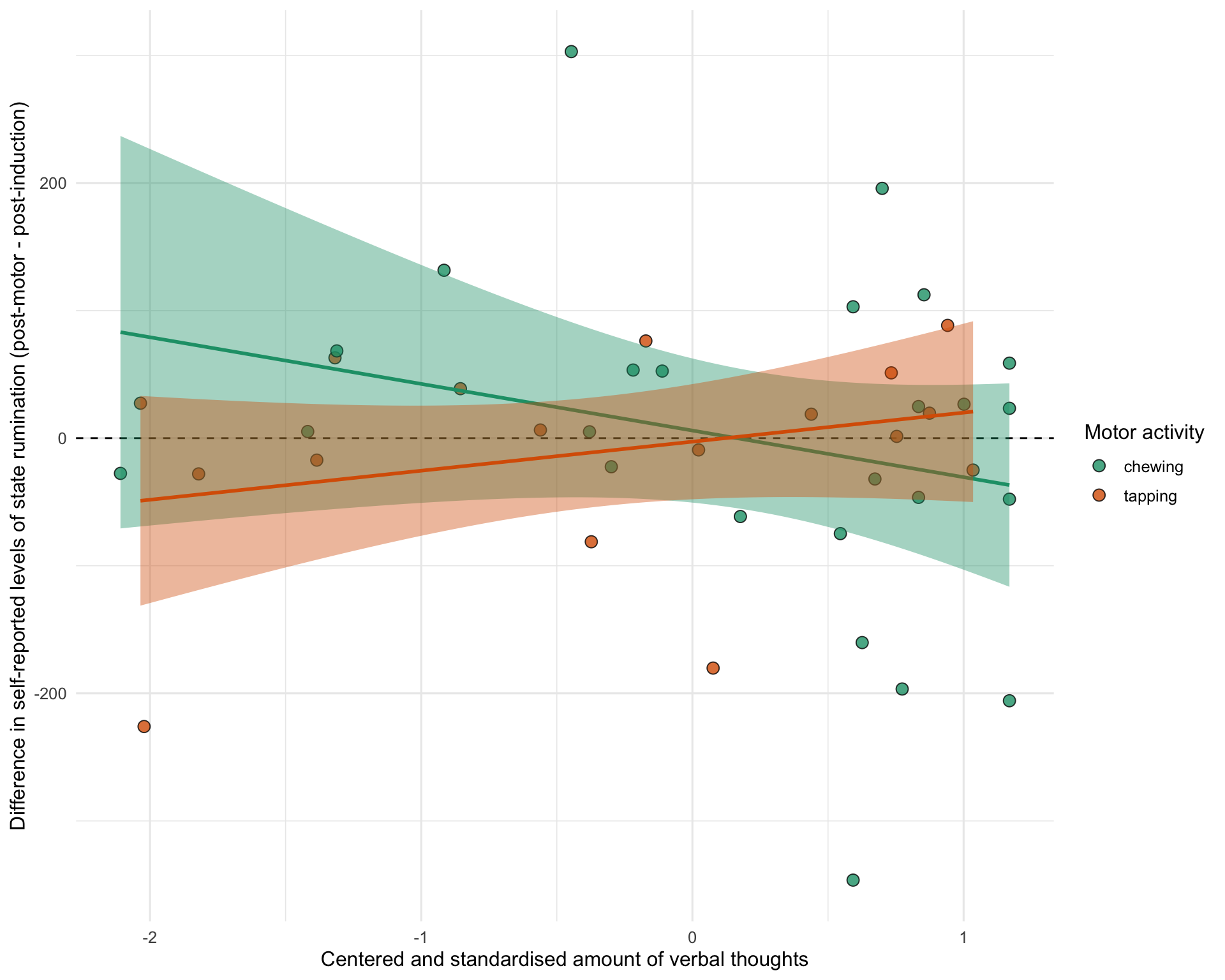

However, because we are interested in estimating the effect of each predictor (and because the amount of data is very low), we report the estimations from the model including an effect of time, motor activity, verbality, as well as two-way and three-way interactions between these predictors. Constant effect estimates for this model are reported in Table 7.6. Based on these values, it seems that the overall self-reported levels of state rumination did not decrease after motor activity (\(\beta\) = 0.617, 95% CrI [-39.291, 36.975], \(BF10\) = 0.194). However, Verbality (i.e., the amount of verbal thoughts) was positively associated with state rumination on average (\(\beta\) = 67.122, 95% CrI [22.673, 107.963], \(BF10\) = 20.359). Interestingly, the interaction between session, motor activity, and verbality indicates that a higher amount of verbal thoughts was associated with a different interaction between session and motor activity (\(\beta\) = 52.098, 95% CrI [-18.253, 125.86], \(BF10\) = 1.038). As three-way interaction effects are better understood visually, we depict this effect in Figure 7.2. This figure shows that higher amounts of verbal thoughts were associated with lower levels of self-reported state rumination in the chewing group and higher levels of self-reported state rumination in the finger-tapping group (as we predicted). However, the estimation of this effect is very uncertain due to the low sample size (as expressed by the large standard error) and should be therefore considered cautiously.56 The overall evolution of self-reported state rumination throughout the experiment by condition is depicted in Figure 7.3.

| Term | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Rhat | BF10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 282.714 | 22.392 | 239.053 | 328.215 | 1.001 | 2.254*10{}16 |

| Session | 0.617 | 19.581 | -39.291 | 36.975 | 1.000 | 0.194 |

| Motor activity | 45.413 | 42.107 | -40.091 | 125.173 | 1.000 | 0.72 |

| Verbality | 67.122 | 22.159 | 22.673 | 107.963 | 1.001 | 20.36 |

| Session x Motor activity | -7.903 | 35.669 | -78.474 | 63.638 | 1.000 | 0.352 |

| Session x Verbality | -6.808 | 18.910 | -45.599 | 27.575 | 1.000 | 0.199 |

| Motor activity x Verbality | 38.577 | 39.515 | -41.372 | 114.926 | 1.000 | 0.66 |

| Session x Motor activity x Verbality | 52.098 | 34.925 | -18.253 | 125.860 | 1.000 | 1.038 |

Figure 7.2: Interaction between session, motor activity, and verbality. The x-axis represents the amount of verbal thoughts reported by the participant. The y-axis represents differences in self-reported state rumination from after the induction to after the motor activity. Dots represent individual scores.

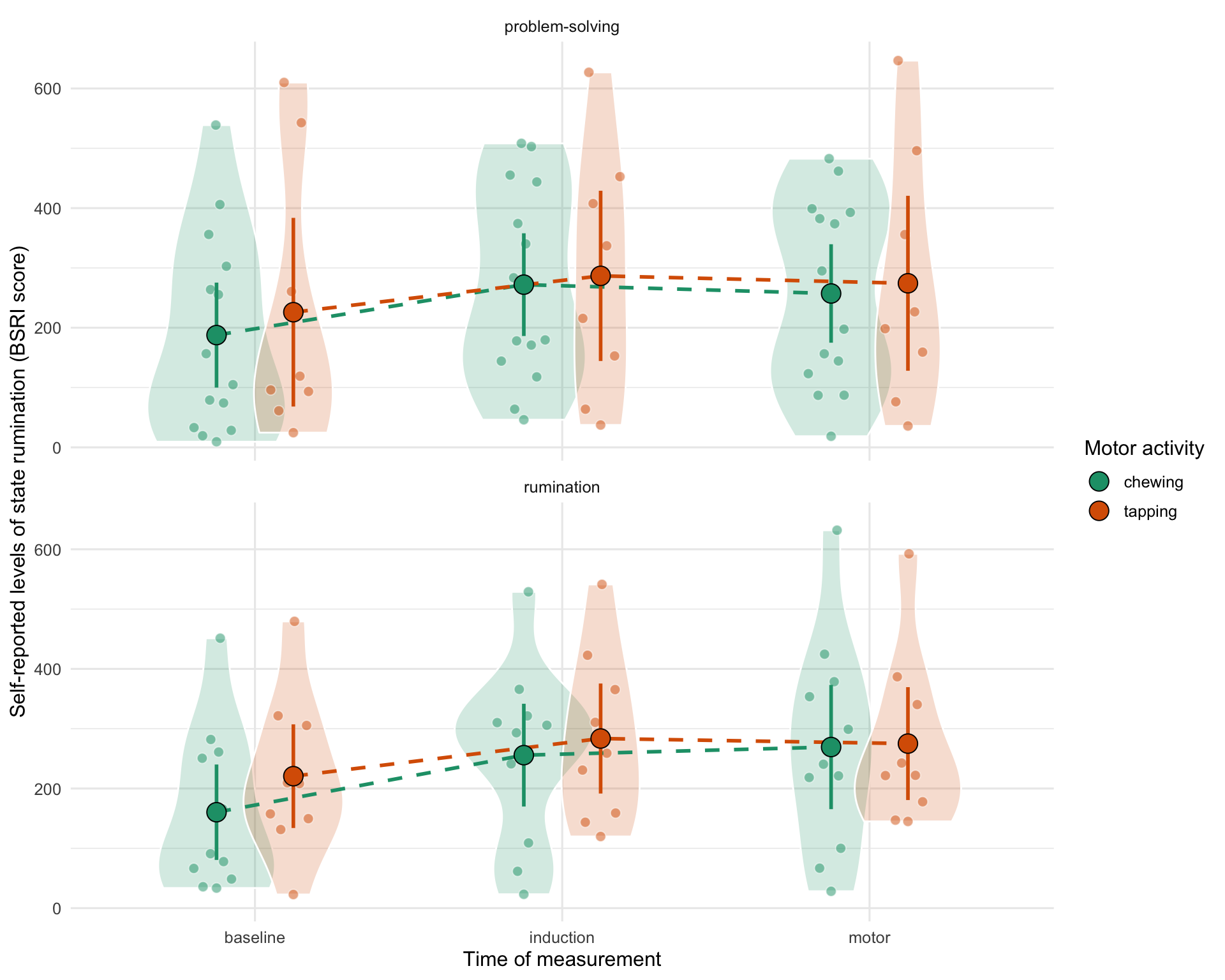

Figure 7.3: Average self-reported levels of state rumination (BSRI sum score) throughout the experiment, by thinking-style and type of motor activity. Smaller dots represent individual scores.

7.3.2.2 Self-reported negative affects

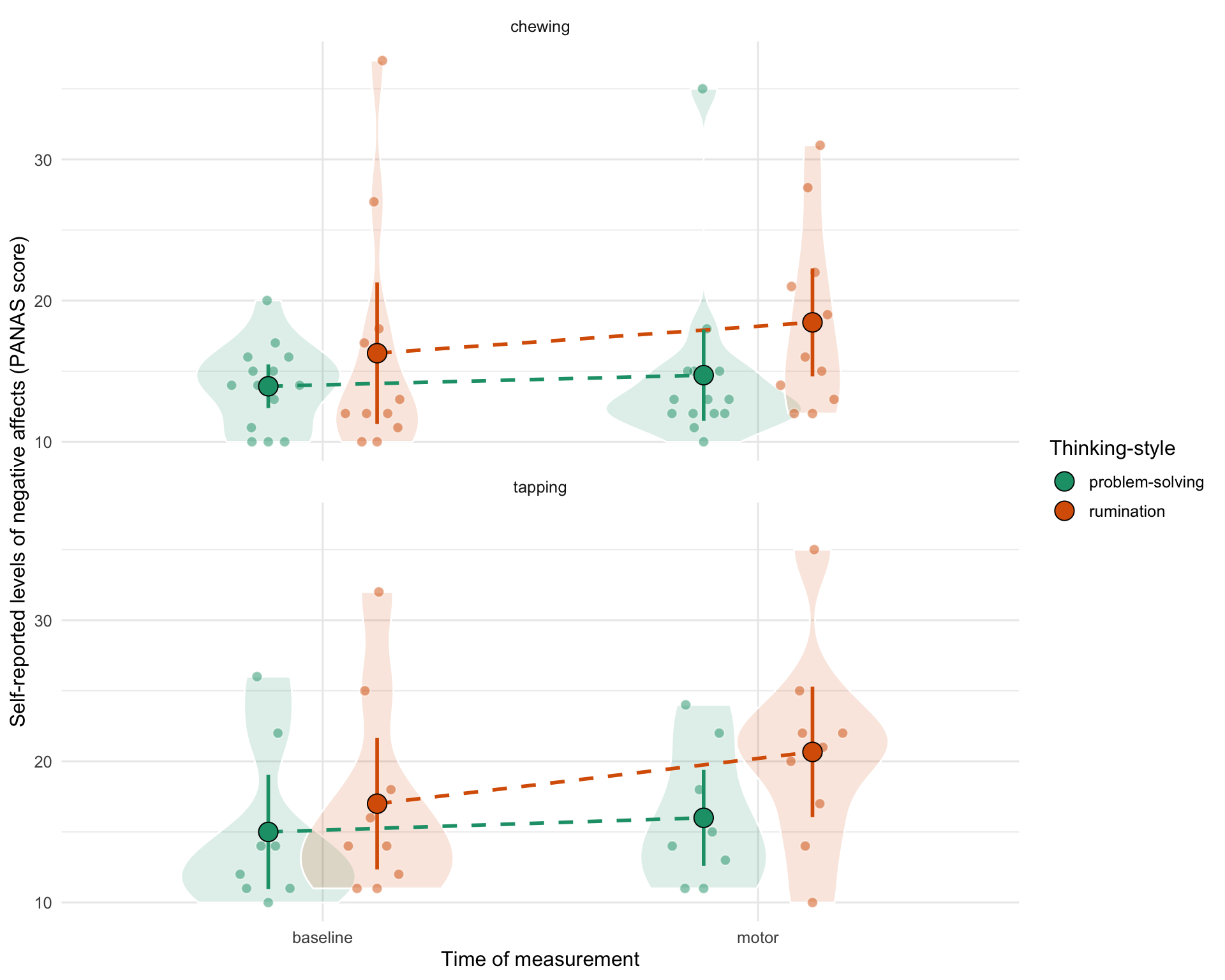

In addition to the self-reported levels of state rumination after each type of motor activity, we were also interested in the self-reported levels of state negative affects. More precisely, we expected an interaction between the type of motor activity (chewing vs. finger-tapping) and the thinking-style (rumination vs. problem-solving). Indeed, as both rumination and problem-solving are expected to recruit inner speech to some extent, we expected both thinking styles to be affected by articulatory suppression (i.e., by gum-chewing). Because rumination is expected to have detrimental effects on mood (assessed via the PANAS score) and problem-solving is expected to have “less detrimental” effects (in comparison to rumination), interfering with these thinking styles should reduce their effect on mood. To assess this effect, we examined the interaction effect between thinking-style and motor activity on the change in negative affects from baseline to after the motor activity (in other words, on the baseline-normalised PANAS score). These data are depicted in Figure 7.4.

Figure 7.4: Average self-reported levels of state negative affects (PANAS) by thinking style and type of motor activity at the beginning (baseline) and end (motor) of the experiment. Smaller dots represent individual scores. NB: colouring and facetting factors have been reversed as compared to the BSRI figure to better highlight the interaction effect.

As previously, we compared several models to examine our hypotheses. Based on our hypotheses, we expected that the model comparison would reveal a three-way interaction between Thinking-style and the type of motor activity. However, the best model identified by the WAIC model comparison did not include this interaction as a constant effect (see Table 7.7).

| \(WAIC\) | \(pWAIC\) | \(\Delta_{WAIC}\) | \(Weight\) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(Int\) | 264.76 | 3.60 | 0.00 | 0.381 |

| \(Int+Think\) | 265.19 | 4.45 | 0.42 | 0.309 |

| \(Int+Motor\) | 266.17 | 4.34 | 1.41 | 0.188 |

| \(Int+Think+Motor+Think:Motor\) | 268.50 | 5.47 | 3.73 | 0.059 |

| \(Int+Motor+Verbal+Motor:Verbal\) | 268.51 | 5.90 | 3.75 | 0.059 |

| \(Full\ model\) | 273.88 | 7.90 | 9.12 | 0.004 |

However, because we are interested in estimating the effect of each predictor (and because these analyses are still preliminary), we report the estimations from the full model (i.e., the model including an effect of thinking-style, motor activity and verbality as well as all possible interaction effects) in Table 7.8. Based on these values, it seems that self-reported levels of negative affects increased from baseline to the end of the experiment (\(\beta\) = 2.031, 95% CrI [0.118, 3.859], \(BF10\) = 0.877). Moreover, the rumination induction led to a greater increase in negative affects than the problem-solving induction (\(\beta\) = 1.938, 95% CrI [-1.853, 5.494], \(BF10\) = 0.32), and the chewing groups also showed a greater increase in negative affects as compared to the finger-tapping groups (\(\beta\) = 1.101, 95% CrI [-2.461, 4.729], \(BF10\) = 0.206). Interestingly, the interaction between thinking-style and motor activity indicates that the effect of the motor activity on the change in negative affect was different according to the thinking-style (\(\beta\) = 1.217, 95% CrI [-6.091, 8.056], \(BF10\) = 0.367). As three-way interaction effects are better understood visually, we depict this effect in Figure 7.4. This figure shows that the effect of the thinking-style on the change in self-reported state negative affects (i.e., the difference in steepness of the regression lines) was different according to the type of motor activity, with a stronger effect of the thinking-style in the finger-tapping condition than in the chewing condition (as we predicted). However, the estimation of these effects is very uncertain due to the low sample size (as expressed by the large standard error) and should therefore be considered cautiously.

| Term | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | Rhat | BF10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.031 | 0.939 | 0.118 | 3.859 | 1.000 | 0.877 |

| Thinking-style | 1.938 | 1.825 | -1.853 | 5.494 | 1.000 | 0.32 |

| Motor activity | 1.101 | 1.768 | -2.461 | 4.729 | 1.000 | 0.206 |

| Verbality | 0.842 | 0.936 | -1.087 | 2.708 | 1.000 | 0.14 |

| Thinking-style x Motor activity | 1.217 | 3.519 | -6.091 | 8.056 | 1.000 | 0.367 |

| Thinking-style x Verbality | 1.357 | 1.866 | -2.345 | 4.940 | 1.000 | 0.232 |

| Motor activity x Verbality | 0.807 | 1.846 | -2.912 | 4.252 | 1.000 | 0.19 |

| Thinking-style x Motor activity x Verbality | 0.580 | 3.491 | -6.316 | 7.749 | 1.000 | 0.345 |

7.4 Discussion

The discussion section will be completed once data are fully gathered and analysed.

7.5 Supplementary materials

Pre-registered protocol, open data, supplementary analyses as well as reproducible code and figures are available at https://osf.io/8ab2d/.

7.6 Acknowledgements

The first author is funded by a PhD fellowship from Univ. Grenoble Alpes. We thank Kim Rens for her help during data collection.

This experimental chapter is a working manuscript reformatted for the need of this thesis. Source: Nalborczyk, L., Perrone-Bertolotti, M., Baeyens, C., Koster, E.H.W., & Lvenbruck, H. (in preparation). Examining the involvement of the speech motor system during rumination: a dual-task investigation. Pre-registered protocol, preprint, data, as well as reproducible code and figures will be made available at: https://osf.io/8ab2d/.↩

These gums were chosen to be as neutral and usual as possible. More precisely, we used sugar-free and allergenic-free mint-flavoured gums.↩

An introduction to Bayesian statistical modelling is outside the scope of the current paper but the interested reader is referred to Nalborczyk et al. (2019a), for an introduction to Bayesian multilevel modelling using the

brmspackage.↩This method simply consists in taking the ratio of the posterior density at the point of interest divided by the prior density at that point (Wagenmakers et al., 2010).↩

Moreover, the relation between the verbal scale and the change in self-reported state rumination following the motor activity looks only vaguely linear, which should make us cautious about the interpretation of the linear estimates.↩